|

RAF

HERSTMONCEUX

During

WW2, the

generating buildings at Herstmonceux served as accommodation

for wounded RAF aircrew, working with the early warning radar

station at RAF

Wartling and RAF

Beachy Head. RAF Wartling succeeded RAF

Pevensey, continuing after 1945 into the 1950s Cold War

period - closing in 1963.

There

is a concrete and brick Anderson shelter in the grounds of RAF

Herstmonceux. Outside the shelter there were two banks of

batteries protected by brick walls that were covered with a

2" concrete slab. This batter store powered a radio

transmitter, the aerial for which was to the left and forward in

the picture above. In 1982, when these remains were uncovered

and rescued from sycamore trees, all that was left of the radio

equipment was a Morse code sender, a seriously rusted away

transmitter/receiver and some of the lead-acid battery plates.

These were completely different in make up to the much larger

industrial batteries that were used 30 years earlier to store

electricity overnight for the village.

The

concrete shelter has substantial steel (RSJ) girders in the

roof. When discovered the roof was covered in about 12"

inches of soil. A sycamore was growing from within the shelter,

out through the doorway, with thick ivy obscuring the existence

of the entrance, making it look like the side of a hill. The

Anderson shelter was used as makeshift accommodation for a

number of years between 1982-1988, then again in the 1990s. This

use at least gave the occupier the incentive to install a

waterproof roof, with a felt covering, to stop the freezing

cycle during winter when water trapped in the cracks, froze,

expanded, and then made the cracks worse. Ivy was also invasive,

getting behind the rendering and pushing it away from the brick

walls.

A

number of red cross stretchers were found on site. The canvas

was pretty moldy and the wooden frames eaten away by woodworm,

but they could have been saved by treatments. Not realizing the

value of this find, only the peculiar steel hinges were salvaged.

Nobody mentioned about the RAF camp in the early years - and the

link to RAF Wartling was not obvious. So, the wooden

frames and canvas were burned.

Lime

Park Heritage Trust are friends with two landowners at the Pevensey

marshes, who are custodians of the extant artifacts on site, and

like us (our curator) have struggled with local authority to

gain recognition. So well done chaps.

WAAF

operator, Denise Miley, RF7 chain home plotter WWII

BATTLE

OF BRITAIN - 12

AUGUST 1940 - CHAIN HOME

By the beginning of August, concentration of Luftwaffe forces in

France had been fully accomplished, creating prerequisites for the next phase of the German offensive – an all-out attack on British aerial defences. On August 1, Hitler issued Directive No.17, ordering the Luftwaffe to use all its forces to destroy the RAF. The operation was given the code name Adlerangriff - Attack of the Eagles. The long-standing British fear that the German air force was capable of delivering a `knockout blow’ on their country was about to be validated.

The following weeks of fierce fighting and attrition stretched the already weakened RAF defences to the utmost.

Activity against British shipping lasted for an additional week. On 8 August, the Germans launched the first of a series of mass daylight attacks, so far still with a Channel convoy as their main target.

At the radar station at Pevensey, young WAAF operator Jean Semple had her first day on duty. Seeing on her screen a blip of what appeared as a large number of enemy aircraft, she informed her male supervisor and suggested him to take over.

His brusque reply did nothing to inspire her confidence: ‘It’s your operation, you do it.’.

At this early time, identifying the number of aircraft from a radar blip was rather difficult, especially if they were approaching in large formation. Individual radar echoes were all coming together, distorting the blip with spikes going up and down – a phenomenon known to radar operators as beating.

Jean counted the number of aircraft as an unprecedented 200 plus. She and her supervisor reported the sighting to Stanmore, which could hardly believe Jean’s figures. Could they be dealing with migrating birds?

The plotter in the filter room at Stanmore said she would have to seek verification from her scientific observer who was looking down on the plotting from the window above. Jean was proved to be right. Not birds but planes. Nearly 200 enemy planes.”

The RAF successfully sent up seven squadrons of Nos. 10 and 11 Groups. Several of them could be directed to excellent positions for attack. At the end of the day, the British claimed 24 German bombers and 36 fighters shot down, while the Luftwaffe decided that they shot down 49 of the opposing fighters. Even if the true numbers were lower, it was the day of the highest scores since the Battle started. Official congratulations followed on both sides of the Channel.

The day also provided another example of how valuable the radar detection and control system developed by Dowding was to the defenders. In preparation for the Adlerangriff, the Luftwaffe could no longer ignore its importance. Obviously, something was helping the British squadrons to intercept the incoming raids, even in poor weather.

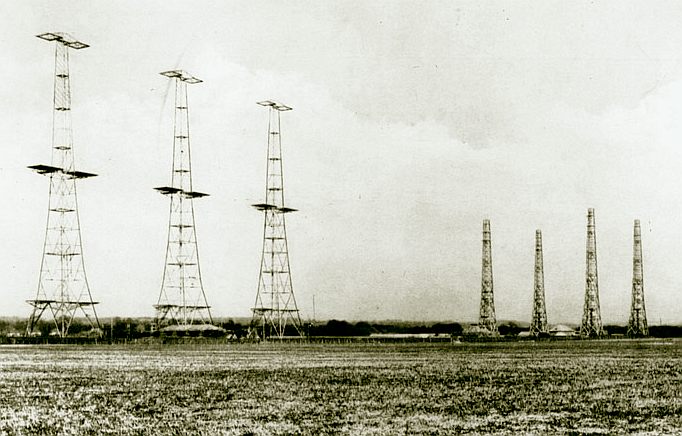

The presence of the British radar was known to the Germans. The 360-foot tall radio masts of the Chain Home stations, visible for miles, had attracted the attention of

German intelligence services since the days of its first experimental installation at Bawdsey Manor. Initially, the Germans were unsuccessful in recognizing the modus operandi of the British radar, mostly due to the fact that their own radar, technically superior to the Chain Home, worked on much shorter wavelengths. However, during July the Luftwaffe set up radio monitoring units along the Channel coast. Their operators soon identified constant, artificial activity on the 12-metre band. Monitoring voice communications over HF radio also revealed that the British fighters were being directed by ground controllers, distinguishable by their consistently calm and clear voices.

On 7 August, German intelligence issued a confidential report on the importance of British radar, stating:

“As the British fighters are controlled from the ground by radio-telephone, their forces are tied to their respective ground stations and are thereby restricted in mobility, even taking into consideration the probability that the ground stations are partly mobile. Consequently the assembly of strong fighter forces at determined points and at short notice is not to be expected.”

It was a misjudgment. Biased by their own radar doctrine, which at the time favoured the use of each radar as an individual unit (such as the one installed by Fink at Cap Blanc Nez, helping him to guide the Stukas towards current shipping targets), the German analysts concluded that each RAF airfield was tied to a single radar with its own, independent ground control. In that they failed to discover the true link between the mysterious masts and voices over the radio. As important as the radar was to the defence of Britain, the true advantage for Fighter Command was in coordinating the data from all Chain Home stations into a single Filter Room. The Filter Room was able to collect, and resolve into a clear picture, what the actual threat was from the numerous, overlapping radar plots reported from various stations. Contrary to the German assessment, it also enabled a single, unified command of all RAF’s fighter resources against the enemy.

Fortunately for the Luftwaffe, even this limited study confirmed the significance of the strange Funkstationen mit Sonderanlagen –

radio stations with special installations as the masts were called in their vocabulary. As a preparatory operation prior to Adlerangriff, the Luftwaffe decided to put them out of action. 12 August went into history as an anti-radar day.

At 9.00, Erprobungsgruppe 210, a specialized Luftwaffe unit operating the novel Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighter-bombers, delivered pinpoint attacks on five radar stations: Rye, Dover, Dunkirk, Pevensey and Ventnor.

“It was the Rye radar that picked them up. It was noticed that the track was heading straight at them. The 19-year-old girl operator was slightly irritated by the way in which the Filter Room, at Fighter Command, gave the plot an X code. That meant a report of doubtful origin: possibly friendly aircraft, or a mistake.

The operators were still watching in fascination as the plot came nearer and nearer. Suddenly bombs began to fall upon them. Almost every building was hit, except the transmitting and receiving block. The Filter Room called repeatedly into the phone to find out what was happening.

“Your X raid is bombing us,” explained the girl primly.”

The radar at Rye was put out of action until power could be restored using a

diesel generator – which happened later during the day. The

Dunkirk site suffered two huts destroyed and damaged transmitting block, but the

radar remained operational. At Dover, some of the

radio towers were damaged and some huts destroyed. In Pevensey, one of the bombs cut the main power cable and the whole station went off the air. The Ventnor site, which around noon was further attacked by a formation of Ju 88s, was set on fire and damaged so badly that it was put out of action for two weeks.

The precision attacks, although unsuccessful in destroying the masts or underground facilities, tore a temporary 100-mile gap in the radar coverage. Exploiting it, the

Luftwaffe launched powerful attacks on convoys in the Thames Estuary and on airfields in Kent – Manston, Lympne & Hawkinge. Portsmouth was also bombed.

These attacks caused severe damage; a clear success for the Germans. And yet,

RAF fighters were not kept out of the scene. During the morning, defences could be partially directed via the untouched radar station at Poling. During the afternoon, most of the damaged stations were sufficiently patched up to get back on the

air, restoring the full operational view in the Filter Room.

On the following day, the German signal intelligence service regretfully reported that none of the British stations had ceased its signals. The British even cleverly masked off the demise of the Ventnor station by transmitting identical signal from another station.

The anti-radar operation of 12 August was not repeated. A few days later, Göring stated,

“It is doubtful whether there is any point in continuing the attacks on radar sites, in view of the fact that not one of those attacked has so far been put out of action.”

It turned out to be one of those costly blunders by the Reichsmarshall.

The

result of so many operational developments is that the marshes

are littered with subterranean artifacts, mainly concrete tracks

and buildings. Linking up many of these buildings are conduits

that fed information via electrical cables (and telephones) to

other buildings. In turn, service tracks and paths were needed

during construction and for servicing. Once decommissioned, all

such evidence soon became overgrown and forgotten, but not here.

We believe that we can learn from the past. No matter that

Germany was our deadly adversary during WWII, this is just

politics and politics changes in times of economic hardship.

Peace then should be achievable with sustainable societies. The

working man and woman should not be burdened with undue taxes to

pay for wars, when wars might be avoided if we plan ahead and

work together globally.

RAF

PEVENSEY

The East Coast Chain Home station at Pevensey was built in 1939. It was originally intended to build the station at Fairlight, east of Hastings but the local landowner objected, considering the aerial masts to be unsightly. In order to provide the same coverage as the proposed station at Fairlight two new stations were required one at Rye and the other at Pevensey. Pevensey was the worst site in the southern group as the whole area was flooded and the buildings were sited in silt subsoil and continuous pumping was needed during the construction. Pevensey faced south (line of shoot) for attack across France from Germany. It was in the right position for the Battle of Britain.

As East Coast stations have only one channel, emergency mobile radars (MRU's) were positioned near each Chain Home station. That for Pevensey was at Chilley Farm to the south west.

As first built, RAF Pevensey covered a considerable area of the Pevensey Levels, now Pylon Farm, but the

radio

transmitters and receivers were housed in sandbagged wooden huts with 90' guyed wooden masts and a mobile generator. This was known as an advanced Chain Home prior to the building of a permanent station.

RAF Pevensey was one of the original 20 Air Ministry Experimental Stations. As originally planned there should have been four 360 foot steel transmitter towers spaced 180ft apart and four 240ft wooden receiver towers in a rhombic pattern set at a distance from the transmitters.

Chain Home was at the forefront of a reporting network resulting in warning data being forwarded to the Fighter Command filter room at Bentley Priory where it was analysed and displayed on the Fighter Command operations table. The information was then told to the Fighter Group HQ's from where the controller allocated the raids to be intercepted from sector airfields and controlled by the sector operations centre during the day and the fledgling GCI radar stations during darkness. The new GCI station, RAF Wartling, built on the opposite side of the road to RAF Pevensey is an example of this, becoming operational during the early years of WW2.

RAF Pevensey was short lived and by December 1945 the station was described as 'caretaking' (Air 25/686 Appendix A) with its future also listed as 'caretaking'. As the station was not required for the post war rotor radar programme both RAF Pevensey and RAF Rye were offered for sale by public auction in Battle (Sussex) in November 1958. The inventory of buildings and equipment offered for sale at the two sites was listed as 'Brick sectional timber and handcraft buildings, 6 350 foot steel towers, 2 water towers and the contents of the buildings including 2 Mirrlees 102 hp diesel engines, electrical equipment and all fittings, steel and timber doors and windows, air ventilation systems, fuel and water tanks, sewage pumps, electric motors, tubular wall heaters, RSJ's, baths, sinks and power cables'.

Pylons Farm

Wartling

East Sussex

OS Grid Ref: TQ644072

CONTACT

US

The

Curator

Lime

Park Heritage Trust

Herstmonceux

Museum

Lime

Park

Herstmonceux

East

Sussex

BN27 1RF,

UK

Telephone:

0044 1323 831727

Email:

energy@solarnavigator.net

|